In 2022, Jon Lauck published The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800-1900. His book highlights the admirable qualities of the 19th-century Midwest, such as its democratic civic ethos, its staunch antislavery stance stemming from the Northwest Ordinance, and the rapid establishment of co-educational colleges. Lauck enriches his narrative with quotes illustrating the Midwestern love of literature, making it a topic of everyday conversation. For instance, he recounts how William Dean Howells, while visiting Representative James A. Garfield in Ohio in the late 1860s, spurred Garfield to excitedly summon neighbors to hear tales of Holmes, Longfellow, Lowell, and Whittier. Lauck’s book thoroughly explains why Americans have reasons to cherish the Midwest’s history.

The release of Lauck’s book should not have been groundbreaking, but it was because the American historical profession has been increasingly dominated by professors who exhibit a profound hostility towards America and Western civilization. Books like Lauck’s are rare today; prominent universities like Harvard, the University of Wisconsin, and Denison College tend to focus on works such as The Children of Lincoln: White Paternalism and the Limits of Black Opportunity in Minnesota, 1860–1876 (2018) and Imagining the Heartland: White Supremacy and the American Midwest (2022). This shift reflects a broader trend in American history departments where the narrative of America’s positive contributions and heritage is being overshadowed by more critical perspectives.

America suffers from a shortage of professors and public intellectuals knowledgeable about our Western civilizational heritage and the principles that formed and sustained our republic. This dearth is particularly acute among historians. While conservative traditions persist in law and economics due to continued influxes of conservative scholars, history departments have become almost exclusively left-wing. This political imbalance, highlighted in Mitchell Langbert’s studies, shows a significant disparity in Democratic to Republican ratios among faculty, particularly stark in history departments. His 2016 and 2018 studies reveal ratios of Democrats to Republicans of 4.5:1 and 5.5:1 in economics, 8.6:1 and 8.2:1 in law and political science, and 33.5:1 and 17.4:1 in history, respectively. This imbalance discourages tradition-minded historians from entering the field, perpetuating the leftward tilt.

The absence of tradition-minded historians has reshaped the understanding of conservative ideals. Tradition-minded scholars in economics and political theory often rely on abstract principles, while tradition-minded lawyers focus narrowly on the law. Historians, however, encompass a broader cultural, societal, and biographical perspective. Their scarcity means that even tradition-minded intellectuals know relatively little about the history that informs their traditions.

This gap in historical knowledge is detrimental to America. Americans are losing touch with their history because there are few tradition-minded history professors to convey it. Radical historians, who often harbor negative views of American history, dominate the field and pass on these perspectives to future K-12 social studies teachers, perpetuating a cycle of historical amnesia and ideological bias.

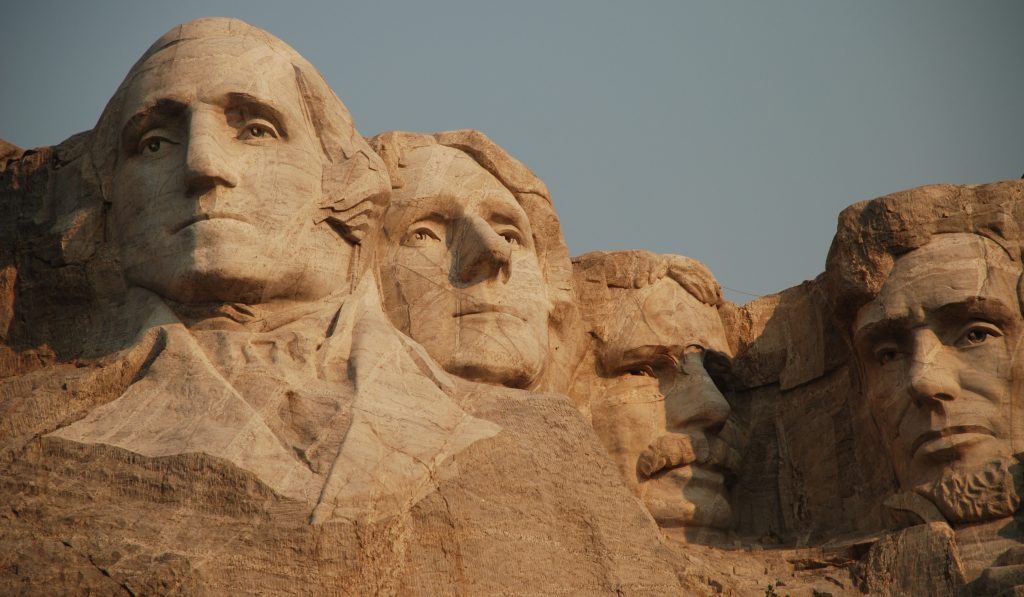

Americans also need a comprehensive understanding of Western civilization—the same history known to the Founding Fathers and influential leaders like Lincoln, King, and Reagan. We require historians specializing in ancient Greece and Rome, medieval Christendom, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, British history, and the history of science and technology. Legal historians are also essential to understanding the interplay between law and liberty.

To counter the radical dominance in history departments, new history departments should be established, staffed by historians dedicated to American and Western civilization. These departments would appeal to students eager to learn about the true history of America and be profitable in the long run. However, creating these departments requires substantial investment and prioritization of resources.

America needs historians who focus on the republic’s constitutional, diplomatic, military, and political history. Additionally, historians should emphasize the nation’s enduring character, ideals, and culture, including intellectual, religious, cultural, social, economic, and technological history. Furthermore, a broad understanding of Western civilization’s history is crucial, particularly the chain of predecessors that influenced America’s ideals and institutions of liberty.

New Centers at public universities in Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas could house these historians and provide competition to the current radical establishment. Tradition-minded philanthropists might also endow such historians in private institutions. Support for tradition-minded historians is more urgent than for political theorists, lawyers, and economists, as historical knowledge is critical to preserving America’s greatness.

Theodore Roosevelt aptly stated that a nation’s greatness lies in its present achievements, supported by a consciousness of past accomplishments. To ensure America’s future greatness, we must cultivate historians who appreciate and convey the significance of America’s past.